Species Recovery

One reason the Forest Preserve District creates prairies, woods and wetlands that contain a variety of native plants is to provide better homes for the native wild animals that live there. But the Forest Preserve District is also working to boost populations of specific animals in jeopardy — namely the Blanding's turtle, freshwater mussels, and the Hine's emerald dragonfly — to give them an even better chance of thriving in their restored habitats.

Blanding's Turtle

Relief for a Rare Reptile

By the end of the last century, the state-endangered Blanding's turtle was already suffering from fragmented and shrinking wetland habitats, and new research was giving ecologists even more bad news. The local population was comprised mainly of adults with few juveniles or young adults: The turtles were dying off faster than they could be replaced.

That's why in 1996 the Forest Preserve District began the region's first Blanding's turtle "head-start" program.

Habitat Loss & Other Threats

By the late 1990s Blanding’s turtles were already in jeopardy in Illinois.

Blanding’s turtles live in wetlands and marshy areas in the Midwest and Northeast but populations are threatened by habitat loss, automobile traffic and predators. The medium-sized turtle can live more than 80 years, but it only reaches reproductive maturity between ages 14 to 20 years. In addition, a female Blanding's will produce a clutch of only 12 to 13 eggs once per year.

Predators are also one of the Blanding's turtle's greatest threats. In the wild, its predators forage turtle nests and eat the eggs or even small hatchlings! During their 60-day incubation period, 90 percent of turtle nests are destroyed by predators every year. Raccoons are the most voracious predators of Blanding’s turtle eggs and hatchlings, and they will even take juveniles and occasionally the adult turtle. Other predators include the skunk, opossum and mink. Rising populations of these predators in many areas of the turtle’s historic range contribute to the loss of this species and why so few turtles hatch or reach adulthood.

Blanding’s turtles (Emydoidea blandingii) have bright yellow chins and throats and smooth, helmet-shaped yellow-speckled shells. They live in quiet waters in wetlands; shallow, vegetated portions of lakes; and wet sedge meadows. They are chiefly carnivorous and eat snails, insects, crayfish and vertebrates.

An adult Blanding's turtle in dry grasses

One Egg at a Time

Each spring, ecologists use radio telemetry to locate tagged and gravid (pregnant) adult female Blanding’s turtles in DuPage forest preserves, which they take to the Urban Stream Research Center or Willowbrook Wildlife Center. The females are induced into labor, and the eggs are collected and incubated in nurseries.

Each female is numbered and identified — as are the eggs she lays — to provide a scientific record of each mother and clutch of baby turtles that are entered into a database containing DNA and other genetic history. When the female is done laying eggs and ready to be released back into her natural habitat, she is fitted with a radio transmitter on her upper shell, or carapace, to make it easier to locate her next year.

After the eggs hatch, turtle hatchlings are numbered and given a medical checkup to determine their weight, length and general health. They are kept and reared for about a year, outfitted with a microchip for identification purposes and then released back to the preserves.

Since its inception in 1996, the District has hatched more than 4,000 Blanding's turtles from wild and head-start mothers under the program. In recent years, at least 90 percent of the fertile eggs recovered resulted in hatchlings. In 2013, 204 fertile eggs were collected and hatched, creating an unprecedented 100 percent hatch rate.

A Blanding's turtle hatching from its shell

Our Partners

Since the program began, the Forest Preserve District has expanded it to include Cosley Zoo, Peggy Notebaert Nature Museum, Brookfield Zoo, Hickory Knolls Discovery Center, Isle a la Cache Museum, Shedd Aquarium, and Phillips Park Zoo. Research has also been conducted with many local institutions such as Benedictine University, University of Illinois, Loyola University, Wheaton College, Western Illinois University, Northern Illinois University and Governors State University.

Our partnerships allow us to expand and improve the head-start program, a collaborative effort that has a much greater chance for success and impact than would our single agency tackling species' recovery on its own.

Blanding's Turtle Releases in DuPage Forest Preserves

Freshwater Mussels

In spring 2017 the Forest Preserve District began releasing native freshwater mussels cultured and reared at its Urban Stream Research Center at Blackwell Forest Preserve into the West Branch DuPage River. Throughout the year it released a total of 24,377 mussels along 13 miles of the waterway.

Release efforts came about after extensive efforts with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and DuPage County Stormwater Management to improve conditions in and along the river by creating in-stream habitat for aquatic animals, combating erosion, and improving the waterway’s ability to store and handle floodwater.

True to its aquatic conservation mission, the District has led efforts to augment native freshwater mussel populations in DuPage waterways to improve water quality. Despite their size, mussels provide enormous benefits because they take in large amounts of water when they feed. In the process, they filter out bacteria, algae, detritus and many other microorganisms before passing clean water back into the river. Just one adult can filter up to 18 gallons of water in one day, and because many mussels like to live in groups, together they can filter enough water to lower overall water pollution levels.

Habitat Loss & Other Threats

Freshwater mussels comprise the most imperiled group of wildlife in North America. At one time, 80 species made their home in Illinois. Today 17 species are extinct, and 23 are listed as endangered, threatened or of special concern at the federal or state level. Man-made changes to rivers have damaged the sand-gravel habitats mussels prefer, ammonia and other contaminants threaten young mussels, and invasive species such as zebra mussels have reduced native populations.

Freshwater Mussels reared in captivity

District crews prepare mussels for release

Introducing mussels to their new home

Hine's Emerald Dragonfly

Scientists estimate Illinois habitats produce an average of just 200 adult Hine’s emerald dragonflies each year. But under valuable leadership from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (including a grant in 2016), the Forest Preserve District is now helping to raise these federally endangered insects in captivity.

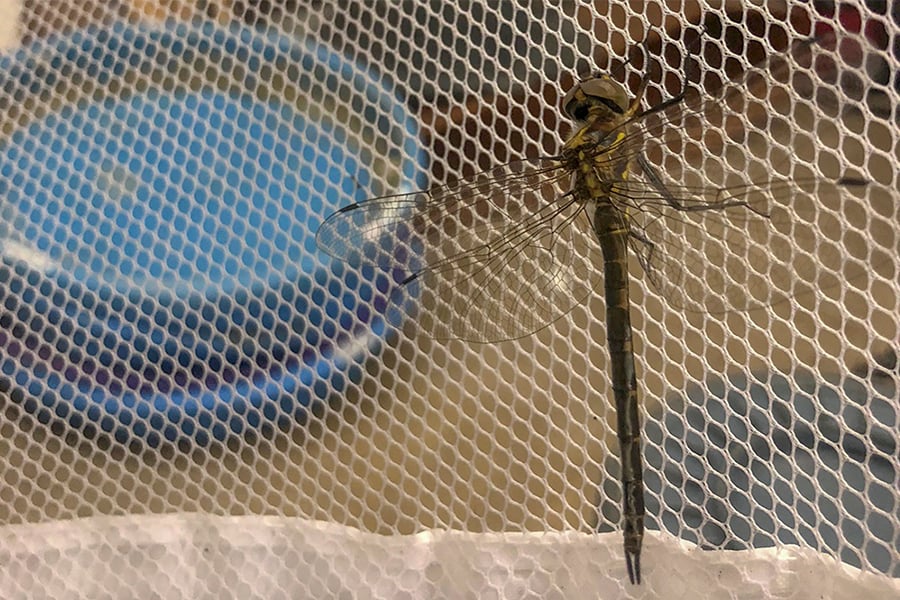

It starts with the University of South Dakota, which collects Hine’s emerald eggs in the wild and raises any resulting larvae for a year or more before sending them to the Forest Preserve District’s Urban Stream Research Center. After two years at the center, the larvae are ready to transform into adults, and ecologists move them to netted “emergence containers” in a DuPage preserve. There, the insects crawl onto the nets and shed their larval skins. Once their winged adult bodies harden, they’re released into the preserve.

By cooperating with other agencies on projects like these, the Forest Preserve District is able not only to operate more efficiently but also to further its mission by creating healthier environments for all inhabitants of DuPage.

Hine's Emerald dragonfly

Raising Great Plains Mudbugs for Dragonflies

To help Hine’s emeralds, the Forest Preserve District is not only raising the dragonflies for release into the wild but also raising Great Plains mudbugs so future Hine’s emerald larvae will have places to call home.

Hine’s emeralds are “aquatic insects.” Adults lay their eggs in the water, and then hatched larvae stay underwater for up to five years as they develop. But Hine’s are picky about the waters they call home. Unlike other dragonflies, Hine’s larvae only live in water at the bottoms of Great Plains mudbug burrows.

One reason for this requirement may be that these crayfish are “primary burrowers.” They build complex burrows deep enough to reach underground water tables below the frost line, which means the water doesn’t freeze. This source of cold open water is critical if Hine’s larvae are to survive winter.

So if an area might be good habitat for Hine’s emeralds but is Great Plains mudbugs and their accompanying burrows, “planting” crayfish is essential. This is where the Forest Preserve District’s new Great Plains mudbug captive-rearing program comes into play. The goal is simple: Raise Great Plains mudbugs in captivity at the Urban Stream Research Center and release them as juveniles in the wild to create breeding grounds for Hine’s emerald dragonflies.

Adult Hine's emerald in an emergence container

Great Plains Mudbug

Hine's emerald Larva

Urban Stream Research Center

The Urban Stream Research Center (USRC) serves as the Forest Preserve District’s facility for aquatic conservation programs and is the only facility of its kind in Illinois. Located where Springbrook Creek enters the West Branch DuPage River in Blackwell Forest Preserve, the building opened in 2012 and was funded by a grant from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). It is the result of a partnership between DuPage County Stormwater Management and the Forest Preserve District.

The center’s main purpose is to augment common native freshwater mussels that were historically more abundant and diverse within the Des Plaines River Basin.

As part of the Aquatic Species Recovery Program (ASRP), native freshwater mussels, which are the most imperiled and vulnerable species in the country, are propagated, reared and released into known historical watersheds, where they are then monitored. Since the center's opening, over 30,000 native freshwater mussels have been propagated at the center and released in local rivers and streams.

The Forest Preserve District manages over 1,100 acres of aquatic habitats, including lakes, streams and rivers. The center also serves as a field research station, partnering with local conservation groups, universities and other institutions on collaborative and applied research in aquatic conservation that seeks solutions to problems facing urban rivers and streams. The District’s Aquatic Monitoring and Research Program surveys the aquatic species and character of rivers and streams on District property.

In addition to the aquatic species recovery efforts and other programs, the center also supports the rearing of federally endangered Hine’s emerald dragonfly larvae and Great Plains mudbugs.

The center is closed to the public, but does offer open houses on select dates. For other information, call 630-206-9620.

Exterior of the urban stream research center

Interior lab operations

species release