Conservationist Fall 2025

From the President

Fall is one of the best times to explore DuPage County’s forest preserves. The air is crisp, the colors are vivid, and wildlife is on the move. From a flash of migrating waterfowl skimming across a lake to the quiet beauty of a frosty morning on the trails, every visit offers something new to discover.

In August the Forest Preserve District and its partners celebrated the restoration of Salt Creek at Fullersburg Woods with a ribbon-cutting ceremony. Restoring waterways like this creates healthier habitats for fish, waterfowl, and other wildlife and enhances the natural beauty of the places we all enjoy. It’s a lasting investment in the future of our community and the land we share.

Speaking of waterfowl, with fall migration underway, ducks, geese, and other feathered swimmers will be using our lakes and rivers (Salt Creek included!) for places to rest and refuel. It’s a great time of year to add a few more species to your birding life list. You can read about many of these dabblers and divers at the bottom of this page.

Exploring the preserves is always fun, and to make it even more enjoyable we recently joined Goosechase, a mobile scavenger hunt app that lets you take on challenges, answer questions, and capture photos as you explore. It’s a playful way to experience nature, whether you’re out with friends, family, or just your own curiosity. Download the app and search for "DuPage Forest" to get going!

As fall progresses, I encourage you to join me in picking a destination from our Forest Preserve District map and stepping outside to see what our preserves have to offer. I hope you’ll find the same sense of wonder that inspires so many people every day, including me!

Daniel Hebreard

President, Forest Preserve District of DuPage County

News & Notes

Collections Corner

The Forest Preserve District has many books in its collections. The majority are in the library at Mayslake Hall at Mayslake Peabody Estate, but a smaller and older collection resides at Kline Creek Farm. The books help the District’s heritage interpreters understand the past so they can share it with visitors.

The 500-page Annual Report of the Illinois Farmers’ Institute from 1898 has been part of this collection for 35 years. The book describes cutting-edge farming technology for the time and shows how farmers have been finding better ways to grow food for decades.

In one report from a evening meeting on Feb. 23, 1898, A.D. Shamel shared research on different types of corn cultivation. The study showed that the biggest effect on yield was soil moisture. Weeds take moisture from the soil, and cultivation gets rid of weeds, but it also opens the soil up to evaporation. This can damage corn plants’ roots, which limits the moisture they get from the soil. The research helped farmers better time cultivation to maximize yield and maintain healthy soil.

During the last two weekends in October you can experience an 1890s corn harvest for yourself at Kline Creek Farm.

2026 Annual Permits on Sale Dec. 1

Annual 2026 permits for off-leash dog areas, private watercraft, archery, and model crafts go on sale Monday, Dec. 1, online.

They will also be available Monday – Friday 8 a.m. – 4 p.m. from Visitor Services at 630-933-7248 or at Forest Preserve District headquarters at 3S580 Naperville Road in Wheaton. Questions? Call Visitor Services at 630-933-7248 or permits@dupageforest.org, or use our chat box in the lower left corner of this page.

Fish Return to Upstream Salt Creek

Recent sampling at Fullersburg Woods has confirmed what conservationists had hoped: Fish are once again swimming freely upstream in Salt Creek following the 2023 removal of the dam.

The Midwest Biodiversity Institute, a nonprofit focused on stream monitoring and habitat assessment, recently completed its first round of sampling following the dam’s removal. The team documented eight native species previously found only downstream of the former dam: smallmouth bass (shown here), northern pike, hornyhead chub, emerald shiner, rosyface shiner, central stoneroller, blackside darter, and logperch. These exciting results show real ecological progress. Fish blocked by the dam are now moving freely, and the stream is on a solid path to recovery.

The removal was part of a larger effort to restore more than a mile of Salt Creek through a partnership between the Forest Preserve District and the DuPage River Salt Creek Workgroup, a nonprofit coalition of local governments, waste-water treatment facilities, environmental groups, and engineers working to improve water quality and stream health. Although funding from the workgroup and its members supports numerous projects in the region, the Metropolitan Water Reclamation District of Greater Chicago funded the majority of the removal project.

Grand Reopening of Danada House

In July the Forest Preserve District celebrated the grand reopening of the historic Danada House. The $6.25 million project was supported in part by a $249,000 grant from the Illinois Department of Commerce and Economic Opportunity’s Tourism Attraction Program.

The comprehensive renovation included exterior restoration, mechanical system upgrades, interior finish improvements, and ADA and life-safety enhancements.

Daniel and Ada Rice built the house in 1939. The District acquired it and the surrounding forest preserve in 1980. Renovations and modifications over the years included the addition of the atrium in 2003 and gardens in 2009.

Event planners can again make reservations for this beautifully restored space through the Friends of Danada at 630-668-5392.

50,000 Plants Added Along Salt Creek

Forest Preserve District and DuPage River Salt Creek Workgroup restoration efforts along the newly restored Salt Creek at Fullersburg Woods continued over the summer with the addition of 50,000 native wetland plugs to areas where invasive plants had previously been removed. Blueflag iris, swamp milkweed, marsh blazing star, and other flowers will support pollinators and add long-term structure to the wetland ecosystem.

In the coming years, another 15,000 plugs and over 350 trees and shrubs will be added throughout floodplains, wetlands, woodlands, and other areas at the preserve.

Thank You for Being a Friend

The Friends of the Forest Preserve District of DuPage County gratefully acknowledges those who donated $500 or more during the prior quarter. The Friends engages the community in philanthropy to advance the District’s mission and master plan for the benefit of wildlife and wild areas and to increase sustainability in the forest preserves.

Learn more or donate at dupageforest.org/friends or mail your gift to the Friends of the Forest Preserve District of DuPage County at 3S580 Naperville Road in Wheaton, 60189. To discuss your giving plans or learn about Friends’ board service opportunities, please contact Partnership & Philanthropy at 630-871-6400 or fundraising@dupageforest.org.

Gift of $15,000 or More

Rich and Nancy Buerger

Gift of $5,000 – $9,999

David and Cheryl Burdine

Domtar

Gift of $2,500 – $4,999

Ferrari Plumbing, Inc

Jeffrey Arthur Jens

Komarek-Hyde-McQueen Foundation

Gift of $1,000 – $2,499

Anonymous

Ann Boisclair

Frances Holbrook

Larry C. Larson

Mary Ann Mahoney

Edith Podrazik

Jerry and Amy Tavolino

Ellen Alekno Wier

Gift of $500 – $999

Anonymous

Coral Baran

Margaret Busic

Donna and John Coffey

Rosemary Conway

Charmaine Cyza

Downers Grove Junior Woman’s Club

Christine Harmon

Allan G. Hins

Jacqueline Lindahl

James Tibensky

Redefining Tick Season

Starting in spring and continuing throughout the hot, hazy summer and into a cooler fall, fans of the outdoors head out to enjoy their backyards and explore the county’s forest preserves. But with the joys of nature comes a tiny often unwelcomed companion: the tick.

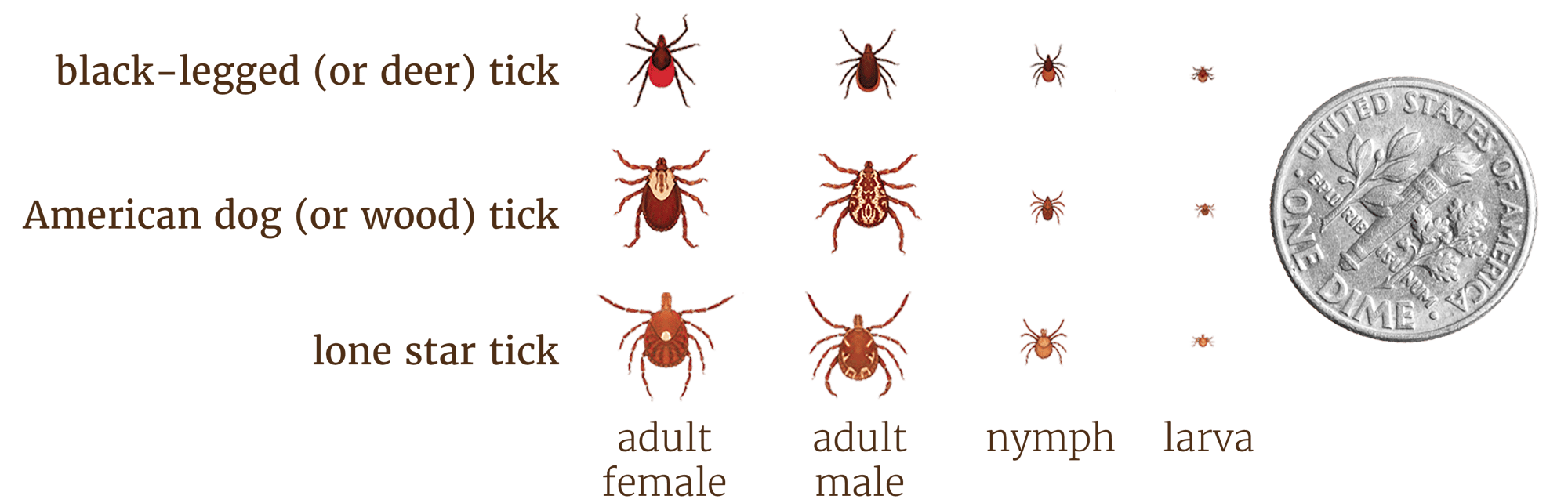

A few different types of ticks live in DuPage. The most common is the American dog tick, also called the wood tick. American dog ticks typically live in tall grasses, brush, and disturbed edges around natural areas, but they also inhabit backyards. Black-legged ticks, aka deer ticks, are well-established in wooded areas with oak leaf litter and wildlife trails. The American dog tick can transmit Rocky Mountain spotted fever and tularemia, but it’s the black-legged tick that can transmit Lyme disease, the most frequently reported tick-borne illness in Illinois. The ticks are most likely to transmit Lyme disease as nymphs, when they are hard to spot, but adults can also carry and transmit the bacteria.

Lone star and Gulf Coast ticks both hail from the southeastern United States, but both are now documented in northeastern Illinois, including DuPage County. Migratory grassland birds and the transportation of tick-infested livestock have played a role in this successful spread north but so has the eight-legged hitchhikers’ ability to survive in new areas where environmental conditions mirror those of their original home ranges.

Ticks have four stages of life: egg, larva, nymph, and adult. After they hatch, though, they must have a blood meal at each stage to survive. Ticks can feed on mammals, birds, reptiles, and amphibians, but many require a different type of animal host for each stage. Ticks that do so can take up to three years to complete their full life cycle, but most die because they don’t find a host for their next feeding.

Even in fall it’s a good idea to tuck your pant legs into your socks if you’re planning an off-trail hike.

Put clothes in the dryer on high heat for 10 minutes to kill any ticks that might have hitched a ride home.

“Tick season” has historically been synonymous with warm-weather months, roughly April through September with peak activity in late spring and early summer when nymphs (pinhead-sized juveniles often difficult to spot) and adults are most prevalent. But if you’ve noticed ticks making an appearance earlier in the year or lingering later into fall, you’re not imagining things. Changing weather and climate patterns are subtly, yet significantly, altering natural rhythms in the environment. Because ticks are incredibly sensitive to temperature and humidity, these changes are reshaping when and where people are likely to encounter them.

Warmer temperatures extend the time ticks are out and about, and DuPage County, like much of the Midwest, is experiencing milder winters with longer periods of above-freezing temperatures. Once rare, it’s now not uncommon to have a series of unseasonably warm days in December, January, or February. For black-legged ticks, which become active when temperatures reach around 45 degrees, this means they can be stretching out their legs in hopes of hooking onto a host (a behavior called “questing”) for more than just a few months in the summer. Milder winters also mean more ticks are likely to survive to the next season, leading to potentially larger populations next summer.

Precipitation plays a role, too. Ticks thrive in humid environments. A dry summer might reduce some tick populations, but consistent or increased humidity can create favorable conditions that allow them to flourish well into fall.

So what does this all mean for fans of the great outdoors? Simply that “tick awareness” needs to be a year-round mindset, not just a seasonal one. Even on a mild winter day or an early spring afternoon, personal precautions are the best defense. (Check out the feature box below for tips.) But by staying informed and taking easy preventative measures, we can minimize risk and continue to safely experience — and enjoy — DuPage County’s amazing preserves.

Tick Tips for Trekkers

Stick to the trails. Avoid walking through tall grass and dense brush.

Dress wisely. Wear light-colored clothes, which makes ticks easier to spot, and tuck your pants into your socks.

Use repellent. Apply EPA-registered insect repellents containing DEET, picaridin, or other approved ingredients as directed to exposed skin and clothing.

Check thoroughly. After spending time outdoors, perform a full-body tick check on yourself, your children, and your pets. Pay close attention to warm, hidden areas like armpits, behind the ears, and the scalp.

Shower. Shower within two hours of returning indoors to wash off any unattached ticks.

Dry clothes. Tumble dry clothes on high heat for at least 10 minutes to dry up any remaining ticks.

Remove ticks. Remove any attached ticks properly and promptly using a pair of tweezers. Then clean the bite site thoroughly. Consider consulting a medical professional for further guidance if any symptoms develop.

Fall Waterfowl

Some of the first animals we learn to recognize as children are waterfowl. We’ve all watched mallards confidently waddling across freshly mowed grass making their way into a nearby pond, the males with their iridescent heads and the females with their elegant subtle palettes. The mallard is by far Illinois’ most common waterfowl, but the group includes far more than just these familiar ducks.

“Waterfowl” is not a scientific term, but it’s commonly accepted to include birds like ducks, geese, swans, grebes, mergansers, coots, and loons, which all spend significant time in the water and tend to be strong swimmers. About four dozen different species have been spotted in DuPage County, many as they stop over during fall and spring migration.

Aside from the occasional encounter (and resulting hiss) with a female Canada goose and her nest, waterfowl are usually docile creatures. In fact, many are skittish and fearful of people. As a result, we don’t always get an opportunity to see them up close. But by comparing sizes, behaviors, shapes, and colors, you can often tell which one you happen to be observing.

For starters, if you want to increase your odds of figuring out who’s who, binoculars or a spotting scope and tripod are both good options. Scopes can be expensive, though, so binoculars are a more practical place to start. A nice overall pick is a pair that’s 8x42. This means they offer eight times the magnification of the human eye and have lenses 42 millimeters in diameter. Bumping up to 10x50 will let you see birds swimming from even further away.

With or without binoculars, knowing the general shapes and sizes of waterfowl can make identification easier. Trumpeter swans, Canada geese, and mallards are three common birds with different features. Swans, the largest, have long elegant necks. Mallards, the smallest of the three, have noticeably shorter necks. But mallards are by no means the smallest waterfowl that visit or nest in the forest preserves. Blue-winged and green-winged teals are smaller, and pie-billed grebes are smaller yet, somewhere between the size of a robin and a crow.

A bird’s relative size can help with identification when you can’t determine feather colors because of lighting or distance.

As for behaviors, first, notice how the bird floats on the water. Grebes and loons sit lower while swans, geese, and ducks appear to have most of their bodies on top of the surface.

Second, how is the bird looking for food? If you recall those mallards in the nearby pond, you might remember seeing them feeding with their heads and necks fully submerged, their little upturned tails and flailing bright orange webbed feet sticking straight in the air. This goofy behavior called “dabbling” is a feeding strategy for certain ducks as well as geese and swans. “Diving” waterfowl on the other hand — mergansers, loons, grebes, and other types of ducks — tuck their wings in and dive bill first into the water, resurfacing in another spot a few to several seconds later, hopefully with a fish, crayfish, or mussel in their grasp.

Mallards “dabble” for food such as seeds and plants but also for aquatic insect larvae, earthworms, and snails.

A bufflehead dives in search of a meal, likely aquatic insects or mussels.

The shape of a bird’s bill can also be a clue, especially when looking at a silhouette in low lighting. Swans, geese, and ducks have more rounded bills; grebes, loons, and mergansers have sharper, pointier bills, which help them as they fish for meals.

Another question to ask is “where’s the white?” Not every bird is going to have white, but most can be identified by taking note of where a white patch, stripe, or wing bar is located. For instance, ruddy ducks and buffleheads are both small diving ducks, and as such, tend to avoid close encounters with people. From a distance, their field marks and color patterns can be difficult to discern. But if you look at where the white is on the head, neck, and body, it’s still feasible to make an identification. A male ruddy duck has white only on a patch on the cheek. The rest of the body appears dark, especially in poor lighting. A male bufflehead, on the other hand, has a thick white headband that starts near the eye and wraps around the back all the way to the other side, fully encompassing the back half of the head. Its chest and belly are also white.

White feathers can help with identification. This male ruddy duck has just a white patch on its cheek.

A male bufflehead has a white chest and belly and white along the entire back half of its head.

Identifying waterfowl in the forest preserves can be a treat, especially when you spot an uncommon species, which happens more than you might think, particularly in fall and winter. Waterfowl are mostly migratory. Many spend summer far north, some above the Arctic Circle. But when the days shorten and the temperatures cool, they head back down our way, many flocking to forest preserve lakes, rivers, streams, and wetlands. Rare sightings have included a white-winged scoter at Mallard Lake, a black-bellied whistling duck at Lincoln Marsh, ruddy ducks at Rice Lake at Danada, and common loons at Silver Lake at Blackwell.

Whether you’re thrilled at the sight of a rare bird on the wing or marveled by a mallard in a neighborhood pond, watching waterfowl is a special way to enjoy the outdoors — just as it was when we were kids.