Conservationist Winter 2026

From the President

For over a century, the Forest Preserve District has worked to protect prairies, woodlands, and wetlands. Today, that mission includes reducing our environmental footprint and preparing the preserves for the effects of climate change. Through our Clean Energy, Resiliency, and Sustainability Plan, we’re identifying ways to save energy, cut greenhouse gas emissions, manage waste, and ensure our natural areas can continue to thrive for generations.

In support of our commitment to clean energy in particular, we’ve installed solar panel arrays at a number of sites. The fleet building at Blackwell; parts of the Danada Equestrian Center; the new net-zero-designed DuPage Wildlife Conservation Center at Willowbrook; and hot water systems, flush toilets, and parking lot lights throughout the preserves are all powered by the sun. Even the electric golf carts at The Preserve at Oak Meadows! And online in 2026, solar panels at Danada will power the District’s headquarters building.

Recently, the District also joined Illinois Shines, a statewide community solar program that allows subscribers to support solar farms throughout the state and receive credits on their electric bills for the power the farms generate. You can read about our participation in this innovative endeavor here.

I’m excited about all the ways the Forest Preserve District is contributing to a cleaner energy future and helping to make renewable power more affordable and accessible for all. Together, we’re certain to ring in a bright 2026!

Daniel Hebreard

President, Forest Preserve District of DuPage County

News & Notes

Collections Corner

Among the many treasures in the Forest Preserve District’s collections, few are as awe-inspiring as the mammoth remains discovered at today’s McKee Marsh in Blackwell.

On June 21, 1977, heavy equipment operator Gary Jones was digging clay from an old bean field when he noticed large bones in the soil. District staff inspected the bones the next day and identified the remains to be from a prehistoric elephant, initially believed to be a mastodon then later confirmed as a woolly mammoth.

Excavation was slow and careful. Staff used hand tools to avoid damaging the bones and set up pumps to keep the muddy site from flooding. They mapped the location of each bone and protected the remains with wet burlap and water to prevent drying.

News of the discovery quickly spread, attracting thousands of curious visitors as scientists and volunteers continued the methodical excavation, ultimately recovering about 75% of the skeleton.

Radiocarbon dating revealed the bones were more than 13,000 years old. Today, this incredible specimen is prominently displayed at Fullersburg Woods Nature Education Center, where it inspires curiosity and wonder in visitors of all ages.

2026 Annual Permits on Sale

Annual 2026 permits for off-leash dog areas, private watercraft, archery, and model crafts are now on sale online.

You can also purchase permits Monday – Friday 8 a.m. – 4 p.m. from Visitor Services at 630-933-7248 or at Forest Preserve District headquarters at 3S580 Naperville Road in Wheaton. Questions? Contact Visitor Services at 630-933-7248 or permits@dupageforest.org.

New Energy, New Savings

The Forest Preserve District is participating in a new community solar program called Illinois Shines that’s increasing the use of renewable energy while lowering District expenses.

In fall 2025 the District entered a 20-year agreement with US Solar, a company that builds solar farms — large fields of solar panels — at various locations across the country. The District specifically subscribed to Illinois solar farms in Oregon and Manville, known as the USS Duck and the USS Man, which will produce and deliver roughly half the District’s annual electricity usage, about 1.7 million kilowatts, to the power grid. In return, the District will receive 10% off its corresponding ComEd bills. Future solar farm subscriptions will offset the District’s remaining 1.8 million kilowatts of usage and result in a 10% savings on remaining energy bills.

These community solar subscriptions come at no cost to the District. Illinois Shines helps to pay for the construction of the solar farms as part of the state’s Climate and Equitable Jobs Act, which requires Illinois to be completely powered by renewable energy sources by 2050. Residents and private businesses can sign up for the community solar program as well but may incur subscription fees. You can read more about this project here.

$10,000 Grant to Support New Greenhouse

As part of their 2025 Green Region Grant Program, ComEd and Openlands, a nonprofit committed to urban conservation in northeastern Illinois, have awarded the Forest Preserve District $10,000 for the construction of a new greenhouse at its native plant nursery at Blackwell. The greenhouse is expected to double the District’s seed collection and distribution efforts, ensuring the protection of local biodiversity and an increase in native pollinators.

The District grows nearly 90 different kinds of native flowers and grasses at its nursery. It spreads seeds collected from those plants across prairie and woodland restoration projects throughout the preserves.

ComEd and Openlands have a long-standing collaboration to create sustainable communities and maintain natural environments. In 2025 they awarded a total of $150,000 to support preservation projects, expand habitats, combat climate change, and create environmental education spaces.

Mayslake Hall 2026 Closure

Starting March 1 the Forest Preserve District will close Mayslake Hall for up to a year for renovations. The extensive project will upgrade mechanical systems to meet code, install ramps on the first floor to aid people who are not able to navigate the stairs, add or replace plumbing so there’s access to water for cleaning purposes on all levels, remove the unused south section of the retreat wing, and upgrade the storage area that houses the District’s collection of historic and natural history artifacts. For updates on these renovations, click here.

Thank You for Being a Friend

The Friends of the Forest Preserve District of DuPage County gratefully acknowledges those who donated $500 or more during the prior quarter. The Friends engages the community in philanthropy to advance the District’s mission and master plan for the benefit of wildlife and wild areas and to increase sustainability in the forest preserves.

Learn more or donate at dupageforest.org/friends or mail your gift to the Friends of the Forest Preserve District of DuPage County at 3S580 Naperville Road in Wheaton, 60189. To discuss your giving plans or learn about Friends’ board service opportunities, please contact Partnership & Philanthropy at 630-871-6400 or fundraising@dupageforest.org.

Gift of $10,000 or More

Robert & Toni Bader Charitable Foundation, Inc.

Gift of $2,500 – $9,999

nora fleming

Edith Podrazik

Stantec Consulting Services, Inc.

V3 Companies, Ltd.

Wheaton Bank & Trust

Gift of $1,000 – $2,499

Anonymous

Autumn Green Animal Hospital, PLLC

The Baran Family Fund

The Conservation Foundation

Friends of Danada, Inc.

Jonathan Kruger

Larry C. Larson

Susan and Craig Manske

Donald and Susan Panozzo

The Richard Laurence Parish Foundation

Monica Sentoff

David A. and Eileen Stang

West Chicago Garden Club

Gift of $500 – $999

Anonymous

Amy Caveney

Paul H. Herbert

Hey and Associates, Inc.

Mark and Jenise Koerner

Barbara Landis-Seid

Mallory Kim Neuberg

David and Amy Phillips

Amy and David Reeter

Rick Stastny

Lisa and Ronald Svegnago

John and Kathleen Westberg

Wight & Company

Thomas R. Williams and Kelly A. Quinn

How to Tell by The Shell

For many, a dip in the water is refreshing on a hot summer day. But for we ecologists who work at the Forest Preserve District’s Urban Stream Research Center, that dip often takes place mid-January in a stream edged with ice.

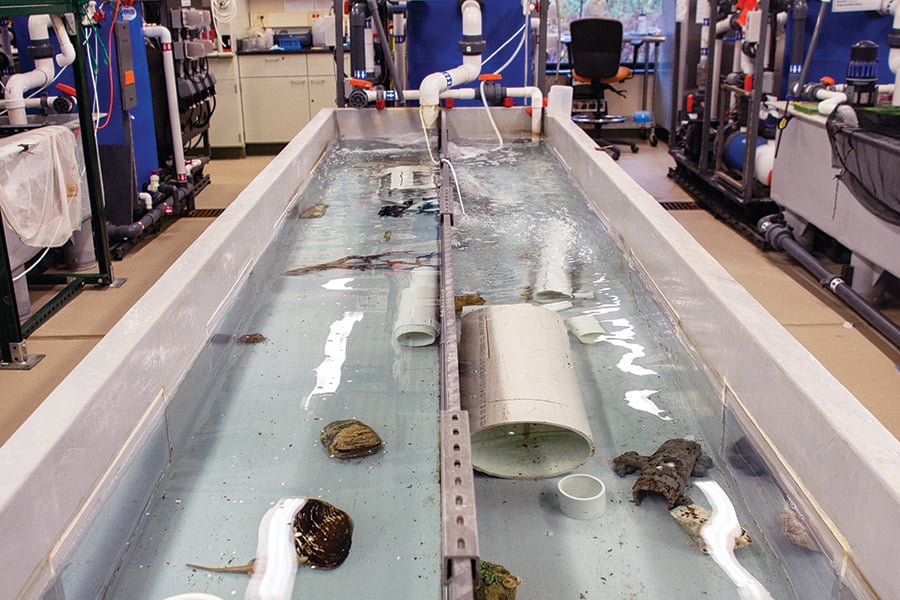

Native freshwater mussels are filtering powerhouses that remove algae, bacteria, and pollutants from local rivers and streams, creating healthy habitats for fish and other aquatic animals. These mussels are also some of the most endangered animals in the world, so for 13 years the Forest Preserve District has been raising them at its Urban Stream Research Center in Blackwell for release into local waterways. To do so, though, ecologists first need to collect pregnant, or “gravid,” females in the wild. Of the nine types of mussels that live in DuPage, seven are only gravid in winter, which means someone needs to get cold and wet.

Thankfully, the process starts in summer, when researchers wade in local waters in search of groups of mussels, recording where they find them. Occasionally, they’ll move individuals to a certain stretch of a river to ensure they can locate them later during the small window when females are gravid, which can be as short as four weeks. Because mussels often burrow in the streambed in winter to avoid near-freezing temperatures, they can be incredibly hard to find, so having a good idea of their general location can help ecologists limit the time they need to crawl through the chilly water.

The author looks for gravid freshwater mussels on a chilly February day.

To make sure they collect the right species, ecologists need to be able to reliably identify mussels in the field without guides or microscopes — a skill that also helps them get out of winter water as quickly as possible! The thing about mussels, though, is that some have distinguishing features while others are more difficult to label.

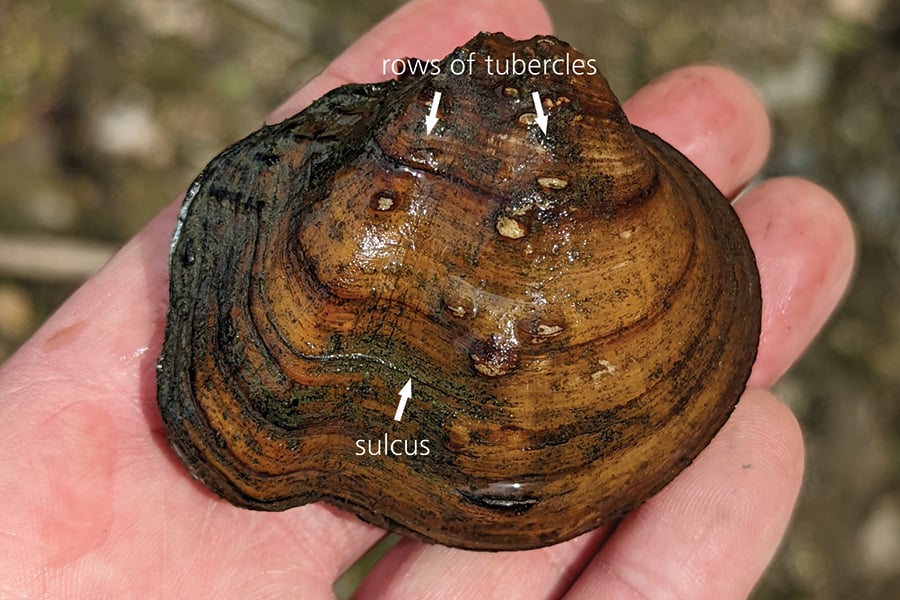

Of the 20 or so species ecologists work with on a regular basis (the District works with partner agencies to raise more than the nine that currently live in DuPage), the mapleleaf is one of the easier to ID. District ecologists first recorded the mapleleaf mussel in DuPage in 2023 as they were working in an unsurveyed stretch of the East Branch DuPage River. They quickly identified it by its distinct appearance, which includes a double row of raised knobs or bumps, called “tubercles,” separated by a shallow, elongated depression in the shell, known as a “sulcus.”

The mapleleaf was an exciting find, but more common species have equally striking appearances. One, the white heelsplitter, gets its common name from a part of its shell called “the posterior wing,” a flattened, often pointy extension at the back of the mussel’s body that can jut out of the riverbed as the mussel burrows. According to legend, the mussel earned its name when the scientist who first described it was walking barefoot through a stream and stepped on one, splitting his heel open. Since then, any mussel with a prominent posterior wing has been called a “heelsplitter.”

In wider northern Illinois, mussels have even more distinct features. One exemplary species (and one of my personal favorites) is the pistolgrip. This large mussel has a thick, elongated, laterally compressed shell with irregularly shaped raised bumps called “pustules” that cover about two-thirds of both halves of its shell. It’s one of the few freshwater mussels that’s sexually dimorphic, which means you can identify males and females just by looking at the shell. Males have shortened, squared-off shells. Female shells are longer and rounder so their gills have the space they need when they’re gravid. (Females carry developing larvae called “glochidia” in their gills before releasing them into the water. Ecologists can tell if a mussel is gravid by looking at its gills.)

A mapleleaf has two rows of bumps called “tubercles” separated by a shallow depression called a “sulcus.”

The white heelsplitter may have earned its name from its sharp posterior wing, which can be painful to step on.

Fully grown pistolgrip mussels can be up to 8 inches long.

Although some mussels are easy to ID, others have just one or two minute discerning features. The giant floater and the creeper are prime examples. Even to the trained observer the two are nearly identical. Only tiny ridges on the “umbo” or “beak” of the shell, the hinge where the two parts of the shell meet, offer a clue. On a giant floater, these markings are called a “double-loop sculpture.” Picture a curvy M or a child’s drawing of a seagull. In comparison, the markings on the beak of a creeper are thickened, raised U-shaped lines.

Whether marveling at the diversity in shells or eyeing that one defining feature, the ecologists at the Urban Stream Research Center are always ready and willing to dive into a river — even one covered in ice — for another opportunity to observe and propagate the freshwater mussels we love and that keep our local waterways healthy and clean.

Ecologists look at fine markings (overlaid above in red for emphasis) on the “beaks” of some mussels to help with identification. Those on a giant floater look like a curvy M.

Creeper mussels have U-shaped markings on their beaks.

Want to learn more about the Forest Preserve District’s work to bring freshwater mussels back to local rivers? Then meet our experts (including the author!) and get a behind-the-scenes look at the Urban Stream Research Center at Blackwell on Jan. 17. Click here to register.

Bundle Up and Enjoy the Show

The short days and long nights of winter can make it a challenge to enjoy the outdoors. By the time most people are free in the evening, the sun is below the horizon, and hunkering down inside seems like the only option. But although the temptation to wait out winter in semihibernation is strong, it would mean missing out on some of the best stargazing of the year.

Winter is the perfect time to admire the stars. First, the nights are darker than in summer. In summer, the Earth’s position points our part of the world toward the dense center of the Milky Way, our home galaxy, which has an estimated 100 billion stars. This means that in July or August, even though we can’t make out all those stars, we’re looking into their light, which gives the sky a hazy appearance. From December through March, though, the sky faces away from the galaxy’s center. Just a thin band of the Milky Way is visible, leaving a lot of empty space.

Winter nights are also colder, which helps with clarity. Warm summer air holds more moisture in the form of water vapor, microscopic droplets that act like tiny lenses, bending and scattering light across the night sky. This produces a bright, hazy appearance that makes stars and planets appear fuzzy.

Cold air with low humidity also means fewer atmospheric disturbances. Think of how the air above a fire or grill appears to shimmer and waver, distorting any objects behind it. The same thing happens on a larger scale above the Earth’s surface in summer. Warmer temps create a more turbulent atmosphere that refracts light before it can reach your eyes. During a cold winter night, however, the air is stiller, resulting in sharper celestial images.

DuPage forest preserves aren’t open at night, but star lovers can get some crisp healthy outdoor air and a look at the stars from their own backyards. Even in developed DuPage County, several celestial objects are visible in winter with the unaided eye. One is an asterism known as the Winter Hexagon.

The term “asterism” is likely not as well-known as “constellation,” but both describe familiar patterns of stars that are easy to pick out in the night sky. The main distinction between the two comes down to global recognition. In the late 1920s the International Astronomical Union designated 88 official constellations. This allowed astronomers worldwide to develop standardized star maps so they could share findings more accurately and efficiently. Asterisms lack this designation. For consistency’s sake the IAU also chose to use names from classic Greek and Latin to label the constellations although cultures worldwide continue to use their own regional names as they have for tens of thousands of years.

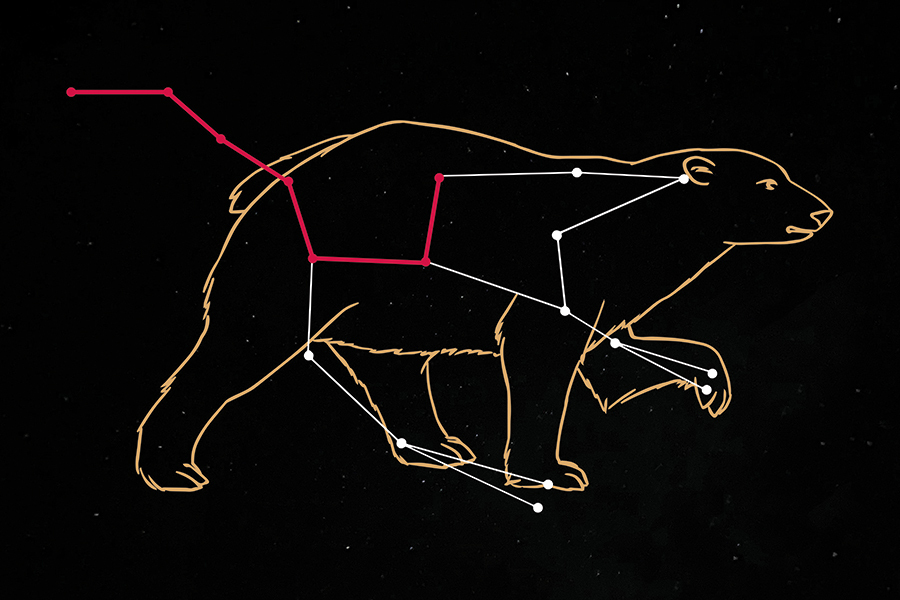

Many times, an asterism is the most visible part of a larger constellation. A prime example is the seven-starred Big Dipper, which is actually a part of the constellation Ursa Major, or the Great Bear. But an asterism can also be formed from the brightest stars of several different constellations. Such is the case with the Winter Hexagon.

The familiar seven-starred asterism known in the U.S. as the Big Dipper, highlighted in red, is part of the larger constellation known as Ursa Major, or the Great Bear.

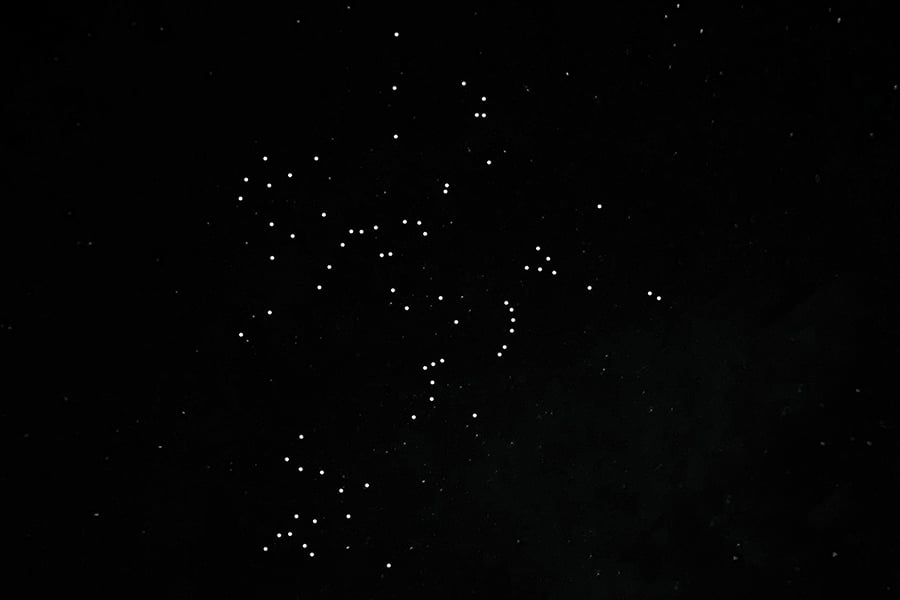

Shortly after sunset, look to the eastern horizon, and you should be able to make out six bright stars in a large loose circle rising high in the sky. This ring is formed by the six brightest stars in the constellations Orion, Taurus, Auriga, Gemini, Canis Minor, and Canis Major, stars named Rigel, Aldebaran, Capella, Pollux, Procyon, and Sirius, respectively. Once you’re comfortable locating the Winter Hexagon, finding other objects is just a matter of some simple star-hopping.

Orion the Hunter is probably one of the easiest constellations to pick out. As soon as the sun sets, look to the south, and you should be able to see Orion in the lower-right corner of the Winter Hexagon. Look for the distinct hourglass shape of his body and the three stars that make up his “belt.”

If you draw an imaginary line through the three stars of the belt and extend it out to the right, the next brightest star you’ll see is Aldebaran, the reddish eye of Taurus the Bull. Taurus is one of the oldest-recognized constellations, dating back to the Bronze Age. Greek stargazers named a smaller V-shaped asterism within Taurus the Hyades after a sisterhood of nymphs who, according to legend, were transformed into stars and heralded the onset of the rainy season. Aldebaran is one of hundreds of stars that make up the Hyades, stars that average around 600 million years old. The majority are red giants or white dwarfs, stars that have used up a majority of their fuel and are entering the final phases of their cycles, burning cooler and giving off more red and orange colors as they do.

Continuing that imaginary line a little further past Aldebaran, you should see a fuzzy cluster that makes up another asterism, the Pleiades, also known as the Seven Sisters. (Auto fans may know this group as the six stars in the Subaru logo, Subaru being the Japanese name for this cluster.) With a pair of binoculars you can see dozens of luminous bright blue stars within the Pleiades, but the asterism actually contains thousands. Their color indicates the stars are extremely hot and relatively young, astronomically speaking, a mere 100 million years old.

Figures in the Night Sky

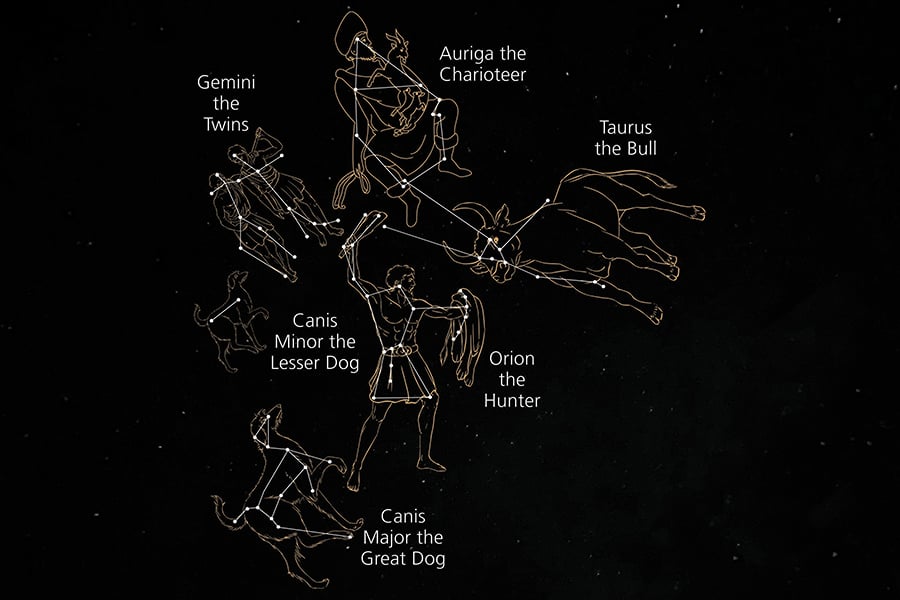

For millions of years the winter night sky in the Northern Hemisphere has included the set of celestial objects shown below.

For thousands of years humans have been drawing imaginary lines between those objects, turning them into fabled people and animals, such as the constellations depicting characters from classic Greek and Latin mythologies illustrated here.

Stories vary, but here, Orion is seen with his two dogs as he confronts Taurus. Twins Castor and Pollux, known as Gemini, spend half the year in the stars, the other half in the underworld. To some, Auriga was a charioteer; to others, possibly a goat herder.

Of course some lights in the night sky aren’t stars at all. One such spot is in Orion. Just below the three stars that make up Orion’s belt hangs his sword. The middle light of that sword is a nebula made up of gigantic clouds of gas and cosmic dust, a mix of carbon, ice crystals, and other ionized particles. Over millions of years gravity will pull these gases and particles together, concentrating their mass and eventually forming the dense hot cores of new stars.

Another bright spot is Jupiter, the largest planet in our solar system. It takes about 12 Earth years for this king of planets to orbit the sun, and in early 2026 this journey will position Jupiter inside the Winter Hexagon near the constellation Gemini. In January, Jupiter will also be “in opposition,” meaning it will be directly between the Sun and the Earth and at maximum brightness. Still, despite being an estimated 89,000 miles in diameter (that’s about 11 times bigger than the Earth), from here, Jupiter will appear as a bright dot slightly bigger than the surrounding stars. With a pair of binoculars and a reasonably steady hand, though, you may be able to see four of Jupiter’s largest moons — Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto — faint pinpoints of light extending in a straight line from the planet’s equator. They’re known as the Galilean moons because they were first observed and described by the 17th-century astronomer Galileo Galilei.

While it may take a bit of bundling up, do your best to get out and under the night sky this winter when conditions will be prime. You may have to deal with some ice, snow, or wind, but there will at least be one advantage — no mosquitoes!

Key Objects in the Winter Night Sky

The photographs in this slide show were photographed with powerful telescopic lenses. To the naked eye they appear as mere pinpoints, but their presence in the sky has fascinated humans for eons. The six stars circled in yellow make up the Winter Hexagon asterism.

Amateur Astronomy Night Pop-Up Programs at Blackwell

The forest preserves aren’t open at night, but we’re planning some special after-hours viewing programs, providing a rare opportunity to observe the stars from Blackwell and to learn how we can all make night skies darker in DuPage. We’ll schedule programs from week to week based on forecasts for clouds and temperatures, so text POPUP to 866-743-7332 and we’ll text you when one is on the calendar!

Photo Credits: header Haryanto/stock.adobe.com; solar panels Soonthorn/stock.adobe.com; seeds © Trevor Edmonson; pistolgrip mussel © Mary; white heelsplitter mussel © Daryl Coldren; mapleleaf mussel © Daryl Coldren; giant floater mussel © Matthew Kvam; creeper mussel © beewilliams; stars with silhouette toshiki/stock.adobe.com; constellation illustrations Claire/stock.adobe.com; Aldebaron David Hajna/stock.adobe.com; Hyades Wirestock/stock.adobe.com; Jupiter Axel Redder/stock.adobe.com; Orion's belt Denis Rozhnovsky/stock.adobe.com; Orion Nebula Irwin Seidman/stock.adobe.com; Pleiades dmitriydanilov62/stock.adobe.com; Sirius Franco Tognarini/stock.adobe.com